Exponential functions and Euler's formula

$\newcommand\R{\mathbb{R}}\newcommand\C{\mathbb{C}}\newcommand\Z{\mathbb{Z}}\newcommand\Q{\mathbb{Q}}$

This post was driven by a desire to explain and prove Eulder's formula, \begin{equation}\label{euler} e^{i\theta} = \cos\theta + i\sin \theta, \end{equation} in a more conceptual way than the standard explanation using power series. Power series are still used as the key technical tool for proving the existence and uniqueness of exponential functions.

Acknowledgements. This was provoked by a Quanta Magazine article by Steven Strogatz on how to prove Euler's formula using power series. The discussion below was inspired by Michael Hutchings' observation that Euler's formula can be proved by solving an ordinary differential equation. I'd also like to thank Dan Lee, Keith Conrad, and my other Facebook friends for their comments and corrections.

Introduction

At first, even the meaning of the left side of Euler's formula \eqref{euler} is unclear. The standard approach is to use power series to define $e^{i\theta}$ and prove Euler's formula. The argument is outlined below. It is simple and elegant. I have, however, always found it unsatisfying, since the power series alone provides little intuition into what's going on.

Here, I provide an alternative approach that I find that is easier to understand intuitively. Moreover, it accomplishes much more. Using only calculus, it provides definitions of the constants $\pi$ and $e$, as well as definitions and basic properties of the exponential, sine, and cosine functions, including Euler's formula.

The exposition here does not require the use of power series. Power series are needed only for the rigorous proof of the existence and uniqueness theorem of exponential functions

Power series proof of Euler’s formula

Here is a brief outline of how to prove Euler's formula using power series. The starting point are the power series \begin{align} e^{x} &= \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{x^k}{k!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} +\cdots \label{taylor}\\ \sin x &= \sum_{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k\frac{x^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!} = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} + \cdots \notag\\ \cos x &= \sum_{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k\frac{x^{2k}}{(2k)!} = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + \cdots. \notag \end{align} It follows by the ratio test that these series converge for every $x \in \R$. The key observation is that these power series also converge if $x$ is complex, extending the domains of these functions from $\R$ to $\C$. Euler's formula now follows by setting $x = i\theta$ in \eqref{taylor} and splitting the series into its real and imaginary parts, \begin{align*} e^{i\theta} &= \sum_{k=0} \frac{(i\theta)^k}{k!}\\ &= \sum_{k=0} (-1)^k \frac{\theta^{2k}}{(2k)!} + i\sum_{k=0} (-1)^k \frac{\theta^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!}\\ &= \cos\theta + i\sin\theta. \end{align*} This is simple and elegant, but the proof provides little intuition to what is going on. Euler's formula appears magically.

Below is an alternative approach that I think elucidates how the exponential function of both real and imaginary numbers arise and why exponential of an imaginary number has a geometric interpretation. The explanation below requires only basic calculus. No knowledge of differential equations is needed. The appendix provides a rigorous discussion showing how to use power series to solve a simple ordinary differential equation. The uniqueness of the solution follows from basic properties of the integral.

Exponential function of a real number

We start by postulating what we mean by an exponential function.

Linear function

We start by with the definition of a linear function. A function $f: \R \rightarrow \R$ is linear if the change in output depends only on the change in input and not on the input itself. More precisely, for any change in input, $\Delta \ne 0$, there exists $c(\Delta) \in \R$ such that $$ f(x+\Delta) - f(x) = c(\Delta),\ \forall x \in \R $$ Observe that $c(0) = 0$. Therefore, if $f$ is assumed to be differentiable, then \begin{align*} f'(x) &= \lim_{\Delta\rightarrow 0} \frac{f(x+\Delta)-f(x)}{\Delta}\\ &= \lim_{\Delta\rightarrow 0} \frac{c(\Delta)-c(0)}{\Delta}\\ &= c'(0), \end{align*} which is a constant. If we set $m = c'(0)$ and $b = f(0)$, this implies that if $f$ is linear, then $$ f(x) = mx + b. $$ The converse also holds.

Exponential functions

An exponential function has a similar definition except that change in output is replaced by relative change in input. In other words, a function $E: \R \rightarrow \R$ is exponential if the percentage or relative change of $E$ depends only on the change in input and not on the input itself. More precisely, for any $\Delta \in \R$, there exists $C(\Delta)$ such that \begin{equation}\label{relative-change} \frac{E(x+\Delta)-E(x)}{E(x)} = C(\Delta). \end{equation} Observe that $c(0) = 0$. From this, it follows that, if $E$ is differentiable, then \begin{align*} \frac{E'(x)}{E(x)} &= \lim_{\Delta\rightarrow 0}\frac{E(x+\Delta)-E(x)}{E(x)\Delta}\\ &= \lim_{\Delta\rightarrow 0}\frac{C(\Delta)-C(0)}{\Delta}\\ &= C'(0) \end{align*} This implies that $C(\Delta)$, as a function of $\Delta$, is differentiable at $\Delta = 0$, and $$ E'(x) = \kappa E(x), $$ where $\kappa = c'(0)$ is a constant.

The following holds:

The proof of existence is given in the Appendix. The proof of uniqueness is below.

Given $\kappa \in \R$, let $e_\kappa$ denote the unique function such that \begin{equation} e_\kappa’ = \kappa e_\kappa\text{ and }e_\kappa(0) = 1 \end{equation} The function $e_1$ will be called the standard exponential function.

Observe that if $E$ satisfies \eqref{ode}, then by the uniqueness statement of the theorem and the chain rule, $$ E(x) = e_0e_1(\kappa x),\ \forall x \in \R. $$ In particular, $$ e_\kappa(x) = e_1(\kappa x),\ \forall x \in \R. $$

Uniqueness of exponential functions

Also proved in the Appendix is that if $e_0$ and $\kappa$ are positive, then the function $E$ given by \eqref{ode} is positive and strictly increasing. This proves uniqueness of $E$ by the following argument.

Let $E_1$ and $E_2$ both satisfy \eqref{ode}. It follows by the quotient rule for differentiation that $$ \left(\frac{E_1}{E_2}\right)' = \frac{E_2E_1'-E_1E_2'}{E_2^2} = \frac{E_1}{E_2}\left(\frac{E_1'}{E_1}-\frac{E_2'}{E_2}\right) = \kappa - \kappa = 0. $$ Since $E_1(0) = E_2(0)$, it follows that $E_1 = E_2$.

Translation invariance

The most important property of the function is called translation invariance, which says that for any $\kappa \ne 0$, $$ e_\kappa(s+t) = e_\kappa(s)e_\kappa(t),\ \forall s, t \in \R. $$ This follows from the fact that if $s$ is held fixed, each side defines a function that satisfies $$ E_s'(t) = \kappa E_s(t)\text{ and }E_s(0) = e_\kappa(s). $$

Relative Change in Output of an Exponential Function

For any function $E$ satisfying \eqref{ode} and any $x, \Delta \in \R$, \begin{align*} E(x+\Delta)-E(x) &= e_0e_\kappa(x+\Delta) - e_0e_\kappa(x)\\ &= e_0(e_\kappa(x)e_\kappa(\Delta) - e_\kappa(x))\\ &= e_0e_\kappa(x)(e_\kappa(\Delta) - 1)\\ &= E(x)c(\Delta), \end{align*} where $$ c(\Delta) = e_\kappa(\Delta) - 1. $$ From this, it follows that a differentiable function $E$ satisfies \eqref{relative-change} if and only if it satisfies \eqref{ode}.

Euler’s constant $e$

We define Euler’s constant to be \(e = e_1(1).\)

By translation invariance, it follows that for any nonnegative $k \in \Z$, $$ e_1(k+1) = e_1(k). $$ By induction and that $e_1(0)=0$, it follows that $$ e_1(k) = e^k. $$ Also, since $$ 1 = e_1(0) = e_1(k+(-k)) = e_1(k)e_(-k), $$ it follows that for any positive integer $k$, $$ e_1(-k) = e^{-k}. $$ Therefore, for any $k \in \Z$, $$ e_1(k) = e^k. $$

For any rational number $\frac{n}{d}$, where $n \in \Z$ and $d \in \Z_+$, \begin{align*} e^n &= e_1(n)\\ &= e_1\left(\frac{n}{d}+\cdots+\frac{n}{d}\right)\\ &= \left(e_1\left(\frac{n}{d}\right)\right)^d \end{align*} It follows that \begin{align*} e_1\left(\frac{n}{d}\right) &= (e^n)^{\frac{1}{d}} = e^{\frac{n}{d}}. \end{align*} In short, for any $r \in \Q$, $$ e_1(r) = e^r. $$

These properties justify the following definition: For any $x \in \R$, we denote the standard exponential function by $$ e^x = e_1(x), $$ which satisfies \begin{align*} e^x &> 0,\ \forall x \in \R\\ e^0 &= 1\\ e^{x+y} &= e^xe^y,\ \forall x,y \in \R. \end{align*} Note that if $x$ is irrational, this is the definition of $e^x$.

Moreover, any exponential function $E: \R \rightarrow \R$ can be written as $$ E(t) = e_0e^{\kappa t}, $$ where $e_0$ and $\kappa = E'(0)/E(0)$ are constants.

Exponential of an imaginary number

Definition

Now suppose you want to extend the definition of $e^t$ to $t \in \C$. Let us focus first on the case $t = i$. One possible approach is defining this is setting $$ e^i = e_1(i). $$ But this is problematic, because it would mean trying to solve \eqref{ode} with $t$ being complex instead of real. A better approach is to use \eqref{ode} as a template and define $$ e^i = e_i(1), $$ where $e_i$ satisfies the equation \begin{equation} e_i' = ie_i\text{ and }e_i(0) = 1. \label{ode2} \end{equation} By Theorem A in the appendix that there is a unique solution $e_i: \R \rightarrow \C$ to \eqref{ode2}. Moreover, for any $t_1, t_2 \in \R$, $$ e_i(t_1 + t_2) = e_i(t_1)e_i(t_2), $$ which justifies writing, for any $t \in \R$, $$ e_i(t) = e^{it}. $$

Geometric properties of the exponential of an imaginary number

We now want to understand the function $e^{it}$ better. An unexpected twist is that geometry and trigonometry naturally appear in the description of this function.

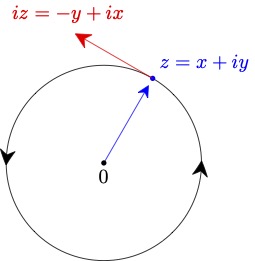

If we write $e_i(t) = x(t) + iy(t)$, then \eqref{ode2} is equivalent to the system \begin{align}\label{ode3} (x',y') &= (-y,x)\text{ and }(x(0),y(0)) = (1,0). \end{align} A solution to this satisfies $$ (x',y')\cdot (x,y) = x'x + y'y = -yx + xy = 0. $$ Therefore, $(x(t),y(t))$, $t \in \R$, is a parameterized curve whose velocity vector $$ v = (x', y') $$ is always orthogonal to the position vector $(x,y)$. It follows easily from \eqref{ode3} that \begin{align*} x^2 + y^2 &= 1\\ (x')^2+(y')^2 &= 1. \end{align*} The first equation says the curve always lies on the unit circle centered at the origin. The second says that the speed, which is the norm of the velocity vector, is always equal to $1$. Putting this all together, we see that the solution is a unit speed parameterization of the circle.

Since the parameterization has unit speed, it is intuitively clear that, as $t$ increases, the solution $(x(t),y(t))$ to \eqref{ode3} goes around the entire circle at least one. In particular, there exists $T > 0$ such that $$ e_i(T) = e_i(0). $$ The translation invariance of \eqref{ode2} implies $$ e_i(t + T) = e_i(t). $$ A function with this property is called periodic.

Definition of $\pi$

If $T$ is the smallest positive constant such that $$ e^{iT} = 1, $$ the constant $\pi$ is defined to be $$ \pi = \frac{1}{T}. $$ Since, for each $t \in [0,2\pi]$, $$ e_i(t) = (x(t),y(t)) $$ is the point reached by traveling at unit speed along the circle staring from $(1,0)$, we can define the length of the arc from $(1,0)$ to $(x(t),y(t))$, where $0 \le t < 2\pi$, to be $t$. In particular, the circumference of the circle, which is defined to be the length of the full circle is $2\pi$.

The angle in radians from $(1,0)$ to the point $(x,y)$ on the unit circle is defined to be the unique $t \in [0,2\pi)$ such that $$ e^{it} = x + iy. $$

Definitions and properties of trig functions

We can now define the basic trig functions to be, for any $\theta \in \R$, \begin{align*} \cos\theta &= x(\theta)\\ \sin\theta &= y(\theta), \end{align*} where $$ e^{i\theta} = x(\theta) + iy(\theta). $$ In other words, $$ e^{i\theta} = \cos\theta + i\sin\theta. $$ Euler's formula is therefore the definition of the sine and cosine functions.

Straightforward consequences of everything above include $$ (\sin\theta)^2 + (\cos\theta)^2 = 1, $$ Euler's formula $$ e^{i\theta} = \cos\theta + i\sin\theta, $$ and the standard differentiation formulas, \begin{align*} \frac{d}{d\theta}(\sin\theta) &= \cos\theta\\ \frac{d}{d\theta}(\cos\theta) &= -\sin\theta. \end{align*} It is also straightforward to use the symmetries of \eqref{ode2} to derive all of the basic properties of the sine and cosine functions, such as: \begin{align*} \sin(n\pi) &= 0\\ \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{2}+2\pi n\right) &= 1\\ \sin\left(\frac{3\pi}{2}+2\pi n\right) &= -1\\ \cos(2n\pi) &= 1\\ \cos((2n+1)\pi) &= -1\\ \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{2}+n\pi\right) &= 0, \end{align*} where $n$ is any integer. Many trigonometric identities also follow easily by raising $e^{i\theta}$ to integer and rational powers.

Exponential of a complex number

Finally, it is now obvious how to define the exponential of a complex number $z$, namely $$ e^{z} = e_z(1), $$ where $e_z$ is the unique solution to the ODE \begin{equation}\label{ode4} e_z' = ze_z\text{ and }e_z(0) = 1. \end{equation} Again, it is straightforward to show that $$ e^{z_1+z_2} = e^{z_1}e^{z_2} $$ and, in particular, $$ e^{x+iy} = e^xe^{iy} = e^x(\cos y + i\sin y).. $$

Summary

We have succeeded in using only calculus to obtain the following in a natural and intuitive way:

- Definitions of the constants $e$ and $\pi$

- Definitions and fundamental properties of the exponential functions $e^z$ for any $z \in \C$

- Definitions of the trigonometric functions $\sin\theta$ and $\cos\theta$

- Euler's formula

Appendix

Existence and uniqueness of solutions to \eqref{ode}, \eqref{ode2}, \eqref{ode4}

We use power series to prove that a solution to \eqref{ivp} exists. Uniqueness is proved above.

Consider the power series $$ E(t) = \sum_{k=0} c_kt^k. $$ If $E$ satisfies the equation \eqref{ivp}, then that $c_0 = e_0$ and $$ \sum_{k=0}^\infty (k+1)c_{k+1}t^k = \sum_{k=0}^\infty zc_kt^k, $$ which implies that for each $k \ge 0$, $$ c_{k+1} \frac{z}{k+1}c_k. $$ By induction, we see that $$ c_k = e_0\frac{z^k}{k!}, $$ Therefore, the power series for $E$ is $$ e_0\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(zt)^k}{k!}. $$ It is easily checked that by the ratio test for series, the series converges absolutely for all $t \in \R$. We therefore define $$ E(t) = e_0\sum_{k=0}\frac{(zt)^k}{k!}. $$

It remains to show that $E$ really does satisfy the \eqref{ivp}. First, we derive the power series for $E'$ as follows: \begin{align*} E'(x) &= \lim_{y\rightarrow x} \frac{E(y)-E(x)}{y-x}\\ &= \lim_{y\rightarrow x} \frac{1}{y-x}\left(e_0\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(\kappa y)^k}{k!} - e_0\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(\kappa x)^k}{k!}\right)\\ &= e_0\lim_{y\rightarrow x} \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{1}{k!}\left(\frac{(\kappa y)^k-(\kappa x)^k}{y-x}\right)\\ &= e_0\lim_{y\rightarrow x} \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{\kappa^k}{k!}(y^{k-1}+y^{k-2}x + \cdots + yx^{k-2} + x^{k-1})\\ &= e_0\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{\kappa^k}{k!}kx^{k-1}\\ &= \kappa e_0\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{(\kappa x)^k}{k!}\\ &= \kappa E. \end{align*} Since, by the ratio test, all of the series in the calculation above converge absolutely, it is a valid calculation and therefore $$ E' = \kappa E. $$

A solution to \eqref{ode2} goes around the whole circle

Details coming.